There’s a running joke in our family about the number of countries where I’ve gotten a speeding ticket. The most embarrassing was getting pulled over for driving too fast through Kruger National Park in South Africa! Who speeds by safari animals?

I’m obsessed with speed. I want things fast and efficient. I have an unfair bias toward trusting people who follow through expediently. And even on a “leisurely” bike ride with my wife, I find myself treating it like a race. Can we beat last week’s time? How fast can we climb the next hill? Let’s pass the cyclists ahead of us!

I know the limits of my obsession with speed. A career of working across borders, time zones, and personalities slows things down considerably. And in conducting research with global executives on four continents over the last several months, different orientations toward speed emerged as one of the most common sources of friction in global teams.

Why Speed Is So Challenging

Most of us readily relate to the challenges that come with different values regarding speed. We feel it when we travel and we almost certainly experience it when being part of a team. In fact, this is a tension that my cultural intelligence colleague and friend Soon Ang and I have often experienced in working together. I want to align around a direction and execute quickly. Soon wants to iterate several times with the possibility of abandoning the whole thing if it isn’t just right.

Here are a few ways the tension surrounding speed surfaced in our interviews and focus groups with global executives:

Across Borders: In a roundtable discussion with Dubai-based executives, leaders described the vastly different orientations toward time within the Gulf region. In the UAE, there is a race to be first in real estate, crypto, artificial intelligence, and almost every new frontier. Just across the border in Oman, the emphasis is quite different, with leaders describing a higher value on preserving cultural traditions, honoring historical perspective, and maintaining a slower pace of life.

Similarly, when interviewing a Silicon Valley executive, she said, “We really do live by the mantra ‘done is better than perfect,’” yet she acknowledged that this was counterintuitive for her. Having grown up in a German household with a father who was a BMW engineer, precision had been drilled into her from childhood.

Across functions: In most organizations, sales professionals are rewarded for closing deals and creating a sense of urgency, while engineers and compliance officers are rewarded for precision and thoroughness. These tensions are multiplied when the functions sit in different regions or markets. In a Shanghai focus group, leaders described the constant tug-of-war between sales and compliance. One executive recounted a conversation from earlier that day when his Shanghai-based VP of sales insisted, “If we do not act fast, our competitors will crush us.” But his Beijing-based compliance officer pushed back: “When we move too quickly, we end up spending twice as long cleaning up the mess.”

Across generations: Nearly every focus group and interview included discussions about generational differences. The issue of speed emerged when discussing clashing expectations surrounding feedback. Many Gen Z employees want instant feedback with a quick thumbs up or text while older generations often prefer to have a conversation to talk things through before making a decision. Yet many younger employees want a work life that is more even paced and avoids burnout.

Generalizations like these are always risky. A wide variety of forces—family, culture, industry, personality—shape our orientation toward speed. But whatever the source of how we feel about speed, mistrust grows when expectations are misaligned. Fast movers may dismiss slower colleagues as too cautious. Those who prefer a slower approach may view speed as careless. Without cultural intelligence, pace differences cost teams opportunities, trust, and morale.

How We Researched and Framed “Speed”

Given the frequency with which speed differences emerged in this research, some colleagues and I decided to study it more systematically. We designed and tested a way to measure an individual’s orientation to pace, and specifically, the degree to which an individual prefers faster or slower approaches to decision-making and action.

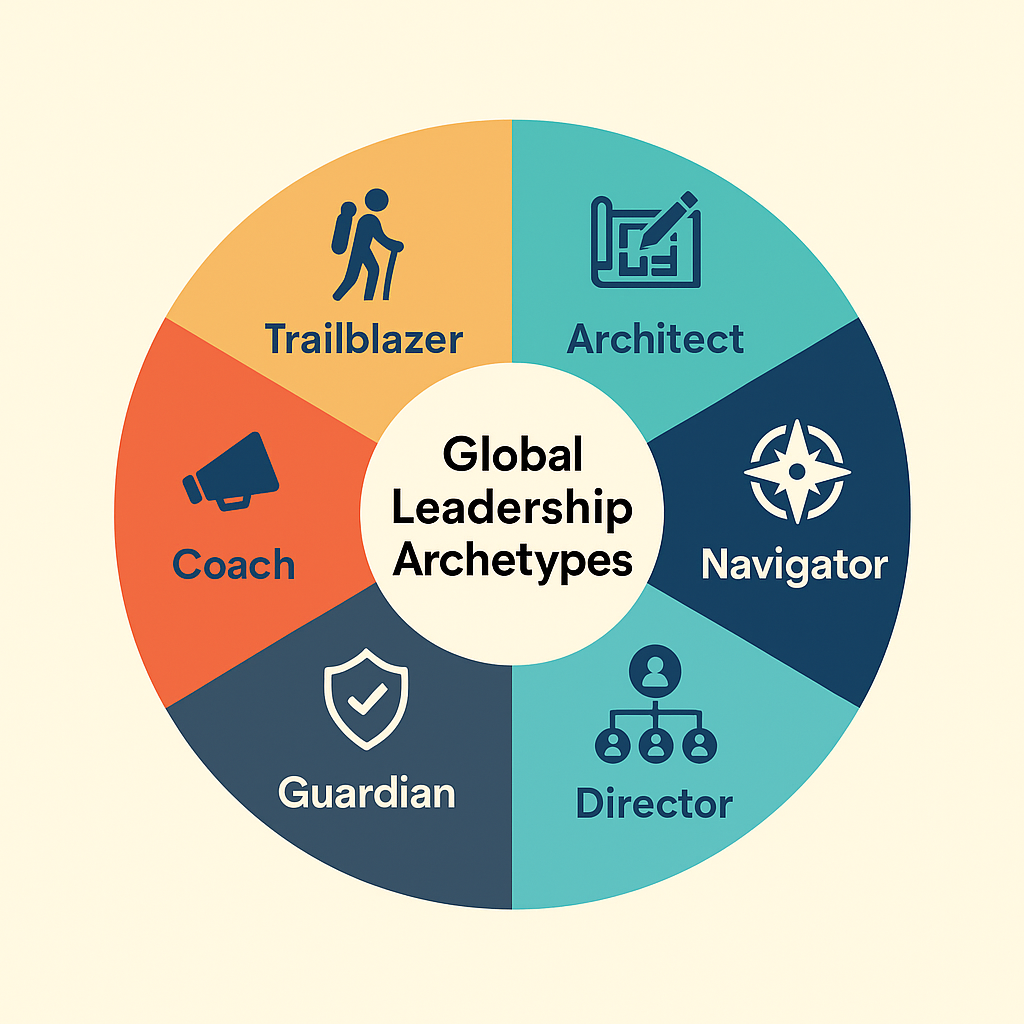

Our investigation was part of a broader framework we’ve been developing, which we now call PRISM, a measurement of five workstyle dimensions: Power, Risk, Identity, Speed, and Messaging. We began our work by revisiting the seminal frameworks for measuring cultural value dimensions, including Hofstede, the GLOBE Leadership Study, Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner, Hall, and Van Dyne and Ang. From there, we developed an initial construct for defining and measuring each of these dimensions, including speed. The construct development was rooted in the kinds of tensions we heard repeatedly in our larger study on global leadership. Our focus was not on aspirational views, but on actual behaviors and preferred workstyles.

For speed, we intentionally narrowed the focus to how different orientations toward pace impact team collaboration. While personality certainly plays a role in one’s orientation toward speed, we were primarily interested in how pace is socialized in us from myriad social contexts. Where we grow up, the industries where we work, the families that raised us, and the cultures we inhabit all strongly shape our expectations surrounding speed. In some contexts, everything feels urgent. In others, things take longer by design.

Next, we tested survey items designed to capture how individuals view pace in real work settings.

A critical task was distinguishing speed from risk orientation. While we found some correlation, with many risk-averse individuals preferring slower decision-making, the two are not the same. In fact, some individuals move faster precisely to avoid risk.

As with all cultural value dimensions, there is no better or worse orientation on speed. A fast approach can energize and capture opportunities. A slower approach can prevent costly mistakes and build trust. The key is learning to recognize and manage the differences.

Strategies for Managing Speed Differences on Teams

How can teams leverage their different orientations toward speed with cultural intelligence? Here are a few suggestions:

1. Measure and Discuss Team Members’ Orientations

Start by surfacing the differences. Ask individuals to reflect on the opportunities and limitations that come with their tendency to move faster or slower. Facilitate perspective-taking: What is it like for someone with the opposite orientation toward speed to work with me? These conversations create language and space for discussing tensions that otherwise go unspoken or are addressed in unhealthy ways.

2. Leverage Both Orientations

Use speed differences strategically. Tap faster movers for projects that require energy, momentum, and rapid iteration. Lean on slower movers when precision, risk assessment, and stakeholder alignment are critical. Leaders can also set clear expectations by signaling the mode: “We’re in sprint mode now” versus “This is our deliberation phase.” Leaders like me need to make sure we’re not in sprint mode all the time. In addition, pairing a fast-moving colleague with one who prefers a slower pace often produces the best results as long as both of them use their CQ. One keeps things moving, while the other asks probing questions and catches details. The tension sharpens the team’s output.

3. Adjust Messaging on Urgency

Urgency itself is culturally coded. Think about a time when a salesperson pushed for a decision before you were ready, so you walked away. There are other times when a company moves so slowly that you wonder if your business even matters to them. Don’t assume that a client or colleague shares your sense of urgency. Find ways to understand their timeline, decision-making process, and observe how quickly they respond and follow-up. This allows you to calibrate your approach. A product launch in one market might highlight the speed and efficiency it will offer; in another market, it might be better to feature the precision and accuracy it affords. This is one of the hardest lessons I’ve had to learn in working around the world. My sense of urgency and pace has nothing to do with whether you feel the same sense of urgency.

4. Create a Team Norm Around Speed

As noted repeatedly in the research on culturally intelligent teams, one of the critical ways to align teams with diverse values and preferences is by creating inclusive, measurable norms. Create a team norm that guides your team’s behavior surrounding timing and pace.

Develop a rule of thumb that is specific enough to guide behavior and avoids defaulting to one side’s preferences. Here are a couple examples:

- “All draft proposals will be circulated within 48 hours of a meeting. Any feedback is expected within one week.”

- “All product launch campaigns need to be tested in at least three markets within six weeks.” (See Leading Global Teams Effectively, HBR for more)

These kinds of norms operationalize the strengths of both orientations toward speed while forcing everyone to make some adjustments for the sake of the shared outcome. Culturally intelligent teams know when to sprint, when to pause, and how to use both orientations to their advantage.

My wife and I recently visited the Azores. A highway sign translated the speed warning from Portuguese into English as “Travel without hurry.” It was exactly the sign I needed to remind me to soak in the slower pace of the environment. But as soon as we entered the airport to head home, I was back to my fast gait and efficiency mindset. I don’t expect my proclivity to speed to change anytime soon and many of my best achievements have been linked to my orientation toward speed and efficiency. But my work is always better when I have partners who slow me down and help me address things I otherwise miss.

We’re not going to change someone’s orientation toward speed. But we can learn to adjust the rhythm that drives how we work together.

—

Later this year, we’ll be releasing the PRISM assessment, along with a corresponding curriculum and certification program. If you don’t already subscribe to CQ Insights, my monthly newsletter, you can do so here to stay up to date on the release.