Most of us appreciate the clarity that comes from learning about broad cultural norms: Indians prefer hierarchy. Germans prefer directness. Brazilians are expressive. Yet we’re less enthused when those kinds of generalizations are applied to us. Someone inevitably pushes back. “I’m from India, but working in Silicon Valley for 15 years shapes the way I approach conflict more than growing up in Delhi.” They’re not wrong. Nationality is one of the weakest predictors of how we work.

How do we offer the clarity that comes from teaching cultural dimensions like individualism vs. collectivism without perpetuating the very stereotypes we’re trying to disrupt? Leaders need a framework that helps them understand and address work style differences that goes beyond the prevalent models of cultural value dimensions. An executive recently said it to me this way, “I don’t need another training on how cultures are different. I need help aligning a partner in India, a regulator in Brussels, and a board in New York.” I’m excited to share a fresh approach that addresses this very need.

The Limits of National Culture

What team would you expect to have the hardest time working together?

- A. An all Canadian team

- B. An international team of physicians

- C. A team of all South American executives

Traditional cross-cultural management would say that doctors from around the world (B) are going to have a harder time working together than people with a shared national or regional identity are. Yet research says otherwise. A meta-analysis of 558 studies across 32 countries found that occupation and social class are far stronger predictors of workplace values than nationality. Physicians from around the world were more aligned in their work-related values than a random group of people working together from the same country. In fact the studies showed that 80 percent of workplace conflict emerged from conflicting values that had nothing to do with country-specific values.

Nationality is not irrelevant. It shapes our values and behavior. But it only explains a fraction of what leaders confront on global teams. A Japanese company merging with a French one may struggle to integrate more because of the unique organizational cultures than the national ones. Three Americans on the same global team can diverge sharply because one works in finance, another in marketing, and the third in compliance.

Those of us who teach culture caution people against applying cultural norms too broadly. “They’re just starting points” we say, “not stereotypes.” Yet something still feels off. Some cross-cultural experts respond to this tension by applying frameworks created to understand national differences to other contexts, such as describing an organizational culture as “collectivist” or an industry as “high uncertainty avoidance.” But a conversation with the late Professor Hofstede rings in my ears. “David, we must be very careful not to apply my cultural value dimensions to something other than what they were intended to measure—national differences.”

The differences experienced on teams around the world are shaped by myriad factors—organizational culture, industry, generation, gender, age, cognitive style, and yes, nationality. Culture is the accumulation of expectations that guide how we participate in meetings, negotiate deadlines, or handle disagreement. The rewards and incentives tied to sales roles reinforce a value for speed and urgency that directly contrasts with the metrics used in compliance, quality control, or legal. Growing up as an adolescent during the rise of social media shapes how you expect and prefer feedback compared with someone whose formative years were spent in an era of face-to-face evaluation and long-form communication. And participating in a video call as someone with ADHD changes how you process and prioritize information compared with others on the same call.

Leaders don’t necessarily need to understand the source of why team members prefer to work the way they do. But they do need an updated framework for understanding and leading a team with a breadth of workstyle differences.

The PRISM Framework

I’ve spent the last four years working with a team of colleagues to design and validate a new framework for measuring the work style differences that most characterize today’s teams. Our findings are in-press but here’s some background on the way we approached this and the resulting framework.

First, we looked beyond nationality to explore the other forces that shape how people learn to work. We knew nationality was still an important factor but we wanted to more carefully look at the role of race, gender, profession, generational group, cognitive style, industry, and organizational culture. While personality certainly plays an important role in how one works, we isolated personality from our analysis because personality (e.g., extraversion) is largely believed to be an innate trait that is unlikely to change (it’s nature more than nurture).

We revisited the seminal studies on cultural value dimensions, including Hofstede, GLOBE, Trompenaars, Hall, and Schwartz. Then we looked at other ways of understanding socialized behaviors, including the powerful insights provided by Dorothy Holland’s work on figured worlds, an enormously useful concept defined as the social contexts where we figure out how we’re supposed to think and behave. Cultural value dimensions and behavioral preferences are still important for providing insights on why we behave and want what we do. We were interested in learning from this work while looking more broadly at team dynamics.

Next, we set out to measure actual behaviors and workstyles, not aspirational views. Many inventories ask people what they espouse to value rather than how they actually behave. Hofstede’s initial IBM study, for instance, asked employees to rate the importance of goals such as “having good working relationships with managers” or “opportunities for advancement.” These questions reveal aspirations more than behavior. Erin Meyer’s Culture Map survey, though not available for academic review, appears to take a similar approach by asking managers to indicate their preferences on issues such as whether feedback should be candid or diplomatic, or whether decisions should be made by consensus or authority. You see a similar approach in a variety of team diagnostics.These tools surface perceptions and ideals, which are valuable for understanding context, but do not fully capture the work styles that show up in daily collaboration.

The GLOBE study advanced this work by distinguishing between “as is” practices and “should be” values. In our research, we concluded that focusing on actual behaviors and preferred work styles provides the clearest insight for leaders who need to anticipate how teams will act when deadlines loom, conflict arises, or authority is unclear. Leaders are not trying to manage what people think is theoretically best; they are trying to lead teams where members bring concrete, sometimes conflicting, work styles into daily collaboration.

In addition, we focused specifically on workplace-oriented values and norms. Most cultural value frameworks mix how one behaves at work with how one interacts with family, friends, and in their personal lives. People repeatedly say, “My cultural values are very different at home than they are at work.” That’s true for me too. As a result, we narrowed our attention on how one approaches conflict, decision-making, and communication in the workplace.

A critical part of this process was identifying the workplace tensions that leaders described most consistently in interviews, focus groups, and fieldwork. Who makes the decision? How much risk is acceptable? Should the group or the individual be prioritized? How fast should we move? How directly should we say it? These stem from the real-world dilemmas of global leaders, cutting across nationality, organization, and industry.

We looked for the frequency with which a difference in work style emerged in the research and began to design an initial construct. We eventually landed on five work style dimensions, which we call PRISM, an acronym for the five dimensions.

Power: The degree to which people defer to authority, challenge it openly, or expect decisions to come from different levels of a hierarchy.

Risk: The extent to which people move ahead with limited information or hold back until risks are carefully identified and addressed.

Identity: Whether people work best autonomously or as part of a group when making decisions and completing a project.

Speed: How quickly people process information, make decisions, and deliberate before moving forward.

Messaging: Whether people communicate in a straightforward, explicit manner or use more implicit, nuanced approaches to make a point.

We designed items to test these values, once again, prioritizing the workplace application rather than what one might do in one’s personal life. We eventually landed on 3-4 survey items that reliably measure each work style (academic publication forthcoming).

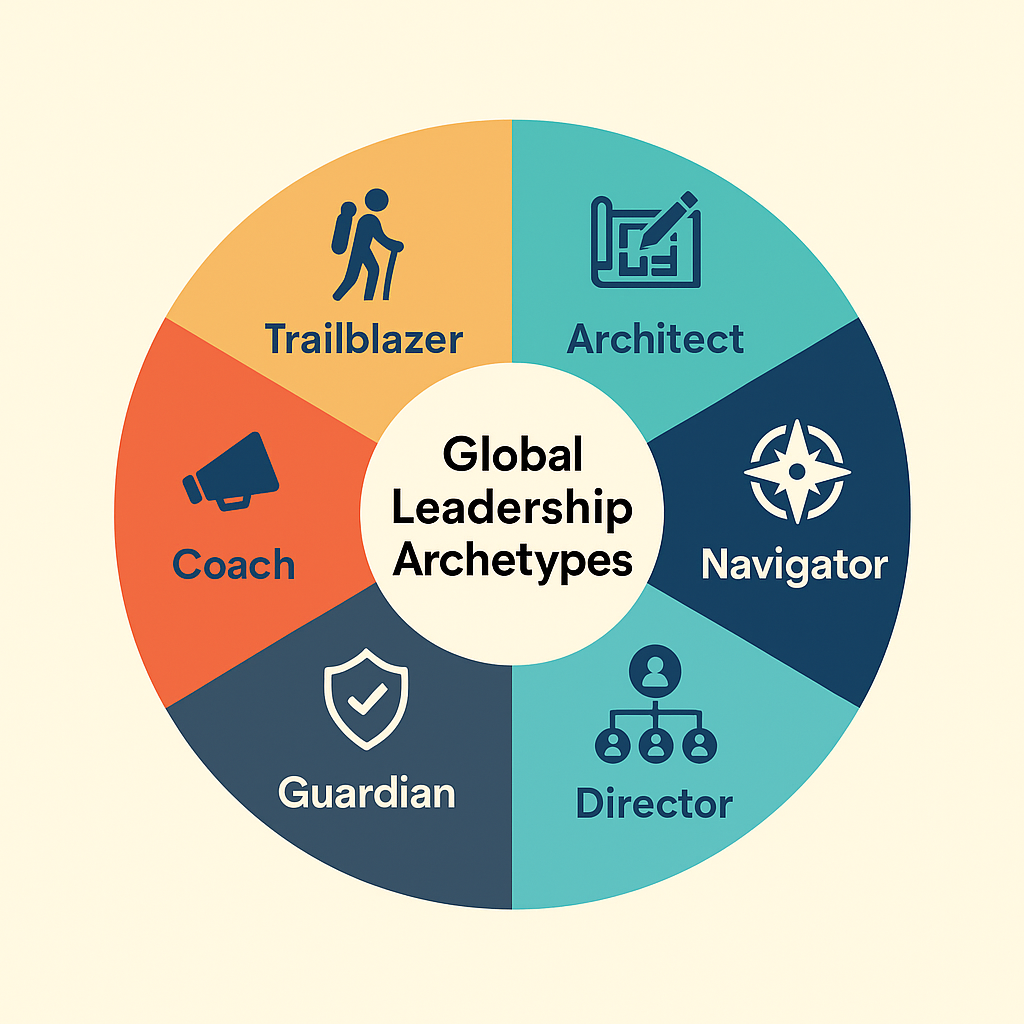

Finally, we examined how unique combinations of PRISM values translate into distinctive leadership profiles. We were interested not only in how individuals scored on each of the five dimensions but in what happens when you have different combinations of these dimensions clustered together. Rather than treating Power, Risk, Identity, Speed, and Messaging as isolated factors, we analyzed the leadership profiles that emerge when different work styles are combined. With ratings across the five PRISM dimensions, each scored at moderate or extreme levels, there are more than 200 possible configurations.

What began as a methodological inquiry became one of the most novel and useful outcomes of this research. A leader who is both risk-averse and direct will lead very differently from a leader who is risk-averse and indirect. Similarly, two individuals may align on four dimensions but diverge on one, such as hierarchy versus egalitarianism, with that single divergence reshaping how they exercise authority and collaborate.

Among the hundreds of combinations, we identified six archetypes that capture the most prevalent leadership styles globally, such as Trailblazers who lead with vision and autonomy (often found in N. America, tech companies, and among neurotypical leaders) or Guardians who lead through protective relationships that emphasize stability and group cohesion (often found in Latin America, family business, and community organizations). I’ll share all six archetypes in a follow-up article because these leadership profiles became one of the most important findings from our study. These six archetypes provide a novel way for leaders to better apply cultural intelligence as they manage diverse teams and organizations.

How Leaders Can Use PRISM

The PRISM survey and profiles will be available soon but there are a variety of ways to apply this kind of model in the meantime. The key is to avoid over-indexing on national differences on one hand or dismissing them entirely on the other. Instead, consider how a broader view of work style differences sheds light on challenges your team already faces. Here are some ways to begin:

- Distinguish work style from performance. Before assuming a team member is underperforming, ask whether their approach to things like risk, speed, or messaging simply differs from others on the team.

- Evaluate work styles informally. Reflect on your own orientation across the five PRISM dimensions and observe how your team members approach authority, pace, and communication.

- Flex your leadership. Notice when your default style works and when it hinders collaboration. Experiment with adapting to the individuals and contexts around you.

- Leverage both sides of a dimension. A team with both high-risk takers and risk-averse members can capture opportunities while still protecting against costly mistakes. The strength lies not in eliminating one side but in integrating both.

Shifting the focus from nationality to a fuller range of work style differences gives leaders a sharper, more practical way to diagnose conflict and align their teams. This is one of the ways we can continue to expand the application of cultural intelligence to ensure it offers a model for leading collaboration in complex, high-stakes settings.

**While the foundational research that led to PRISM included reviewing the work on cultural values, PRISM is not a cultural values framework. Cultural values inventories and the Behavioral Preferences assessment used by our team at the Cultural Intelligence Center provides a critical foundation for understanding WHY individuals behave the way they do. PRISM is focused on team dynamics and leadership styles. It’s one way to apply cultural intelligence, with cultural intelligence and behavioral preferences providing the foundation for any group that has diverse backgrounds.

—

In next month’s article, I’ll share the six leadership archetypes that emerged from our research, illustrating how the unique combinations of PRISM values translate into six distinctive leadership profiles.