I’ve been watching the rift playing out between David and Victoria Beckham and their son Brooklyn, who publicly announced he’s cut off contact with his celebrity parents. I don’t for a moment know the details or credibility of what I’m reading online, nor do I ever take joy in seeing parents and children become estranged. But the public commentary surrounding the Beckhams has been illuminating. Many label Brooklyn as a spoiled, entitled kid who would be nowhere without his parents. And just as many applaud him for protecting himself and his wife from anything that impedes their mental health and well-being.

Gen Z’s impulse to create boundaries and extricate themselves from unhealthy situations is not just playing out in families. It’s one of the most consistent issues that comes up when I talk with managers about where cultural intelligence is most needed on their teams. Last year, I interviewed a Singapore-based executive at a major US multinational whose team includes members from more than six nationalities and multiple generations. She described a situation where two Gen Z employees began blocking a Boomer coworker who upset them, citing mental health concerns. While the leader respected their need for boundaries, she told them, “You can’t just block someone at work. You have to engage, even when it’s hard.” At the same time, she was wrestling with whether there was a better way to handle the situation. As a female leader in tech, she knows firsthand what it means to stand up for yourself.

Why this is showing up now

There’s nothing new about teams at work experiencing generational conflict. Older generations consistently have a hard time adjusting to younger generations’ different ways of going about their work. Adjacent generations in particular seem to have the hardest time getting along. As a Gen Xer, I find it particularly humorous that Millennials seem to be the ones criticizing Gen Z the loudest.

But there’s an additional variable to consider when understanding Gen Z at work. Many parents in Western society brought up Gen Z to create mental health boundaries and encouraged them to name harm and step away from relationships and situations that are unhealthy. Their kids listened and now there’s frustration when Gen Z are quick to call out toxic behavior, disengage from relationships, or say they need a mental health day.

Gen Z has also grown up in a world shaped by social media, constant visibility, and repeated reminders that institutions can’t be trusted to keep people safe. Jonathan Haidt masterfully outlines the impact of the “selfie” on Gen Z, arguing that social media created a new level of comparison with peers. In the US, Gen Z has also grown up with the constant threat of school shootings. It’s not surprising that psychological safety and mental health are top priorities for them. From their perspective, canceling a teammate isn’t about punishment. It’s more about exercising agency, protecting themselves, and preserving a sense of integrity. Even outside the West, many of these values and priorities have permeated the mindset and work styles of twenty-somethings at work.

So what’s a healthy, productive way for team leaders to engage Gen Z at work? Where can teams and organizations adjust to gain the best from Gen Z, and where might Gen Z need to adapt as they become an increasingly important part of the global workforce?

A Conversation Guide for Leaders Working with Gen Z

One effective way to approach generational differences is to treat them like any cross-cultural divide. Lead with curiosity and assume you don’t fully understand.

My friend Steve Argue is one of the leading scholars on emerging adulthood, the life stage where Gen Z currently find themselves. Among Argue’s abundance of evidence-based guidance, here are a couple of my favorites:

- “Tell me more” is good default response when you’re talking with Gen Z. Avoid jumping in too quickly to say you understand. Just as you would do when interacting with someone who holds a different passport, seek first to understand.

- Argue also implores older generations to resist the urge to say, “When I was your age.” We were never Gen Z’s age. While there are patterns every generation experiences, the cultural and technological shifts shaping Gen Z are unlike anything those of us born before the 2000s lived through. Argue says that the pace of cultural and technological change means life experiences overlap far less than they used to.

I would add that for those of us who have Gen Z kids ourselves, it’s not very helpful to make comparisons when talking with our Gen Z team members. Gen Z was raised to be autonomous and to celebrate their uniqueness. When we start to assume we understand Gen Z because we raised a couple ourselves, it can almost sound like a version of a white person saying, “Oh yeah, I have a Black friend,” to prove we understand the Black experience.

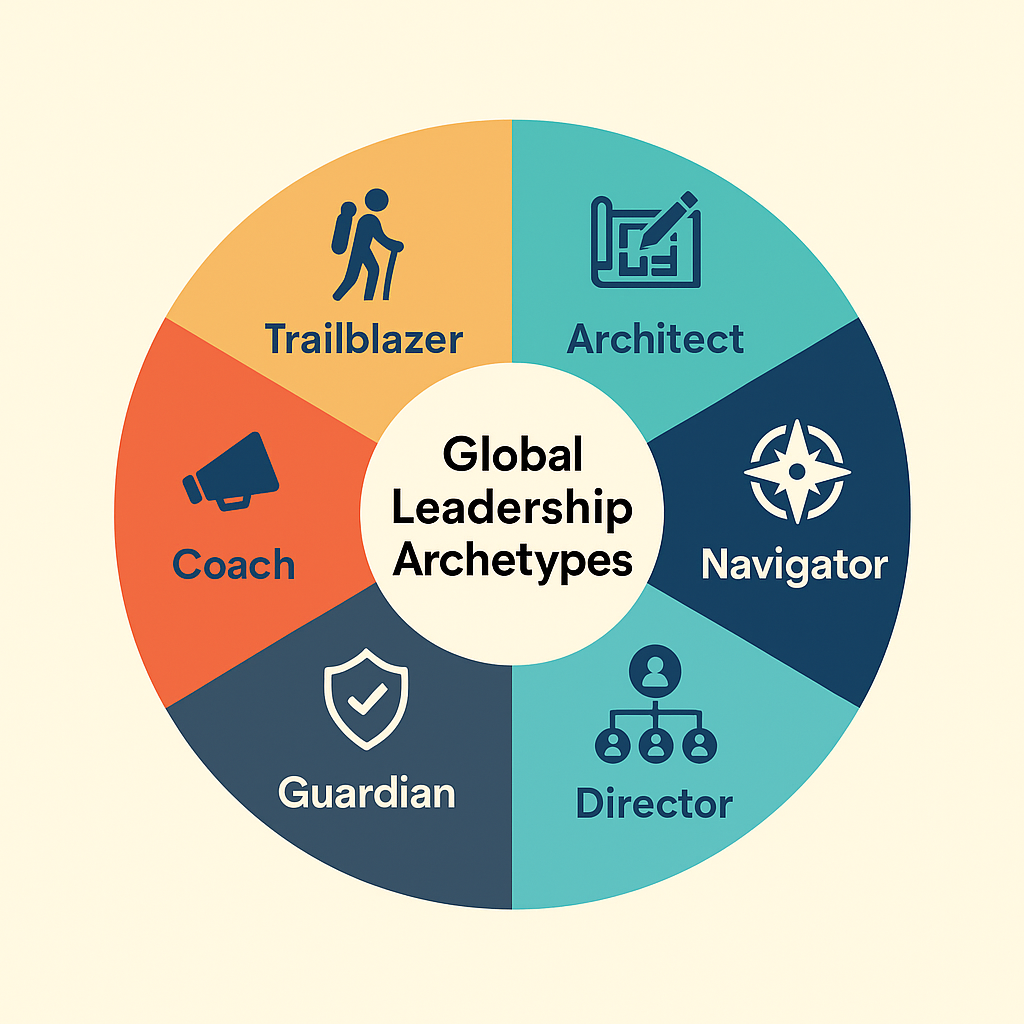

I’ve been thinking about the generational divide throughout my research over the last four years, which has focused on the behaviors that create the most friction on teams at work. Across the data, the same patterns kept showing up and eventually became the PRISM framework: Power, Risk, Identity, Speed, and Messaging. These five dimensions offer a practical way to structure healthy, open-ended conversations with Gen Z at work.

POWER: Flat vs. Top-Down Leadership

The degree to which people defer to authority, challenge it openly, or expect decisions to come from different levels of a hierarchy.

Try asking:

- *What tends to make you disengage or pull back from someone with more authority?

This helps you understand what kind of leadership style allows Gen Z to thrive and why removing contact with someone can feel like the best way to ensure they’re healthy and productive. This prompt may also open opportunities to show how an unfamiliar leadership style might not necessarily be bad.

RISK: Tolerant vs. Averse

The extent to which people move ahead with limited information or hold back until risks are carefully identified and addressed. Ask:

- *How safe do you feel taking risks here—speaking up, disagreeing, or trying something new? What makes you anxious at work?

This surfaces what creates uncertainty and anxiety for Gen Z and may help you understand why disengagement sometimes feels like a way of attaining safety and control. It may also give you insights on how to help them take risks while ensuring your support.

IDENTITY: Self vs. Group-Directed

Whether people work best autonomously or as part of a group when making decisions and completing a project. Ask:

- *When you’re part of a group project, how much autonomy do you need to stay engaged?

Telling a younger team member to just push through doesn’t usually sit right with them. As a generation, they tend to have a different relationship between identity and work than many older team members. While some managers assume Gen Z is more interested in working with a group rather than working autonomously, research doesn’t support that.

SPEED: Faster vs. Slower

How quickly people process information, make decisions, and deliberate before moving forward. Ask:

- *What kind of pace at work brings the best out of you? Can you think of others on your team who might say the opposite?

Gen Z were warned about the danger of an “always-on environment.” It doesn’t mean there aren’t plenty of Type A twenty-somethings working on teams but a lack of control over the pace at which one works is not as easily accepted by them as it has been for other generations. Find ways to talk together about when things may need to move more quickly and when it may be necessary to slow things down.

MESSAGING: Direct vs. Indirect

Whether people communicate in a straightforward, explicit manner or use more implicit, nuanced approaches to make a point. Ask:

- *What tone or words make it hard for you to stay in a conversation?

Words are never just words, and tone matters even more. Communication style is often the behavior difference that creates the most cross-generational conflict, whether it’s via messaging, email, or verbally. Have your Gen Z team members help lead a discussion on what different words and emojis communicate to them. And work as a team to construct team norms about acceptable and unacceptable ways to communicate, ensuring to include norms for those who are more direct and indirect.

Working Together

The purpose of these kinds of questions is for a team leader to learn what’s behind the behaviors that create friction for Gen Z and the colleagues they work with. When leaders create space for these conversations, they reduce the likelihood of silent ghosting or outright canceling and take a meaningful step toward norms that support both psychological safety and shared accountability. And perhaps this kind of approach can help avoid family schisms like the Beckhams’ as well.

——————

To become certified to use the PRISM assessment, framework, and profiles, join our upcoming PRISM Master Certification in April.